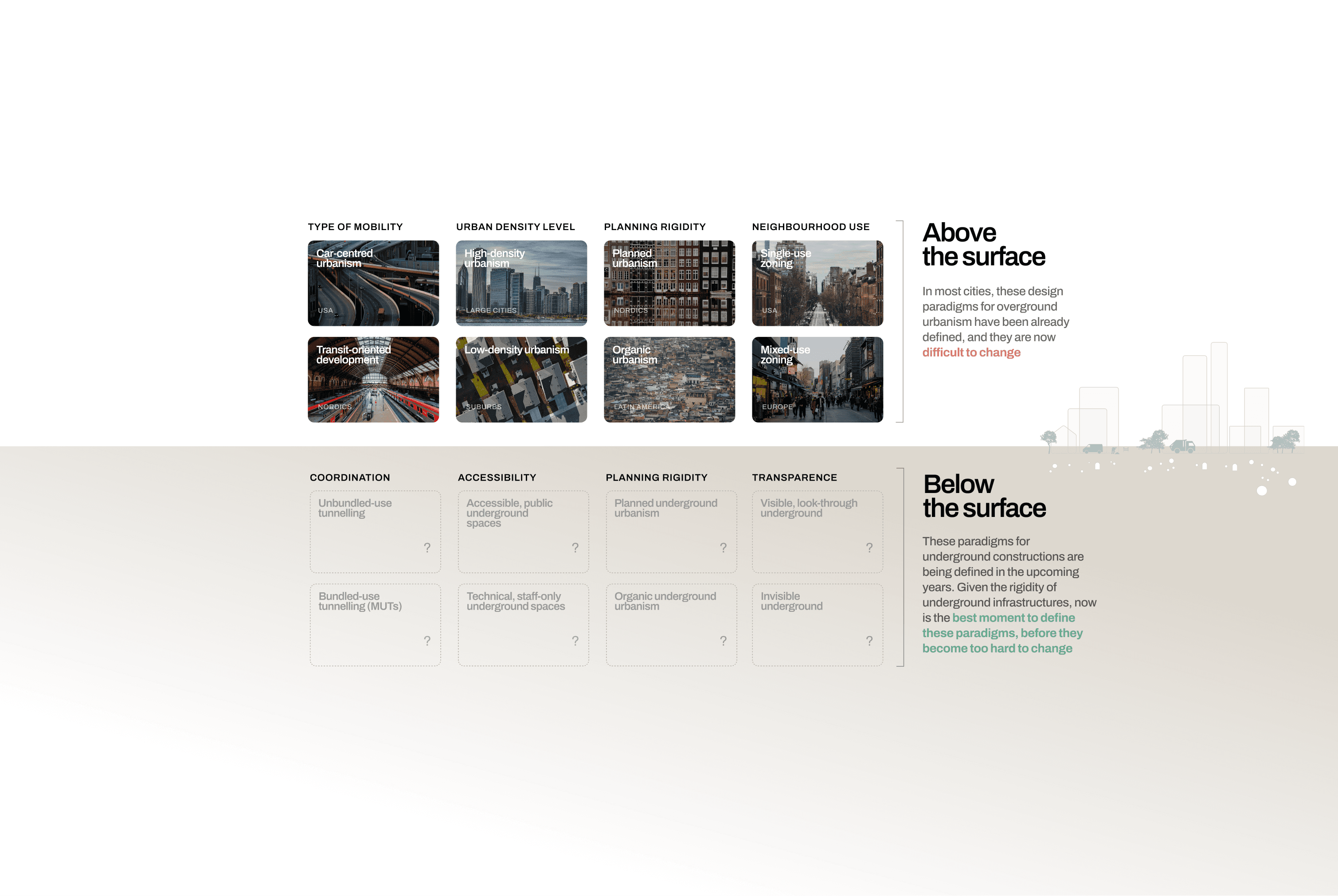

We need to design underground paradigms (before it's too late)

In recent years, the design of urban underground space has become an increasingly urgent system design challenge. Increasing urban density, skyrocketing land prices, and the need for greater urban resilience against extreme climates, have encouraged the creative use of underground space. Clear paradigms should be urgently envisioned before uncoordinated underground infrastructures make it impossible to change them.

Now that underground urban construction is still at its infancy, it is the best time to think systemically and holistically about the future of underground construction.

This article was originally published on Andrea Fanelli's website.

Cities are running out of space

Urbanisation and urban densifications are well-known modern trends, with an estimated 60% of the global population living in metropolises by 2030, up from 37% in 1973. By the same year, 43 megacities are expected to host over 10 million people. This adds new pressure on urban planning, creating the necessity and the economic incentives for a more efficient use of urban space.

With more pressure on city centers, the underground has come to represent a strategic space for adding additional depths to cities.

Underground spaces are a mess

In most cities, the underground is not an entirely virgin space.

The shallow subsurface already hosts a great deal of systems: electricity, gas, water, wastewater, and Internet, all share the shallow subsurface on their way to our homes. Over the decades, these utilities have been sedimenting over each other in a disorganised fashion, leading to a complex bundle of cables and pipes, nicknamed the “spaghetti problem” by some urbanists. In this context, maintenance and renovation are a nightmare. Open-cut trenches are required whenever a pipeline needs to be checked, repaired or renewed — accidental strikes on underground pipes and cables are estimated to cost £1.2 billion a year in the UK alone.

The underground network is currently characterized by an intricate mesh of utility pipes, forming a bewildering and intricate system that is challenging to navigate and susceptible to inadvertent damage.

Deeper down in larger cities, transport infrastructures and underground public spaces have created complex mazes of tunnels and passages, leading in some cases to networks of hundreds of kilometers — like in the example of the Path in Toronto.

In the process of giving the subsurface a larger, systemic role, we are faced with the unique opportunity to rethink and simplify current infrastructures, harmonise utilities, and improve and safeguard maintenance work.

The underground network is currently characterized by a intricate mesh of utility pipes, forming a bewildering and intricate system that is challenging to navigate and susceptible to inadvertent damages.

Resilient cities to address climate change

Meanwhile, climate change is adding environmental challenges to urban spaces. Extreme heat is one challenge. By 2050, an estimated 1.6 billion people in 970 cities may face average summer temperature highs above 35°C, with heatwaves impacting 6x more people than today. Productivity loss due to heatwaves could reach 2 trillion € globally by 2030. In addition, flooding has caused global losses of about 300 billion US$ in the period between 2018 and 2022, together with tragic personal damage and human loss.

While not necessarily tackling the source problem, underground solutions have the potential to increase urban resilience, by means of heat-proof pathways, floodwater solutions, and more.

The result: an increased focus on the underground

The mentioned trends concur to explain the increased focus that urban designers are dedicating to the subsurface. A number of underground mega-projects are currently planned or constructed worldwide, while consortiums and research programs are being built to analyse and design holistic solutions for the underground world.

Underground mega-projects span from electricity tunnels — like the London Power Tunnels, a 2-billion-£ 64-km tunnel carrying high-voltage electricity under the city of London, or the Singapore Power Grid tunnels —, to wastewater tunnels — like the Emisor tunnels in Ciudad de Mexico, or the Stormwater Management And Road Tunnel (SMART in short, and rightly so) in Kuala Lumpur.

The London Power Tunnels, a 64km-long high-voltage electricity tunnel below the surface of London - Source Jason Alden for National Grid

These decades are therefore of central importance for underground urbanism. We are facing the immense risk of building in the subsurface in a disorganized manner, missing out on the opportunity to harmonize the subsurface, create economies of scale, and achieve underground utopias.

A sense of urgency to redesign the underground

While representing substantial urban advancements and technological achievements, these mega-projects fail to display a systemic vision for urban subsurfaces. Even though many cities have greenlighted large underground projects, in most cases the subsurface is only marginally mentioned in their urban planning strategy (such as the London Plan), hence lacking comprehensive policies regarding the use of underground spaces.

The lack of a cohesive, ambitious, systemic vision for the future of underground urbanism is a large problem, and one of a certain urgency. The urgency originates from the fact that underground infrastructures are sticky, rigid to undo. The way we design and build the first underground infrastructures will have a crucial role in defining the paradigms for underground urbanism, similarly to how the first black lines on a white canvas largely define and influence the final drawing.

These decades are therefore of central importance for underground urbanism. We are facing the immense risk of building in the subsurface in a disorganized manner, missing out on the opportunity to harmonize the subsurface, create economies of scale, and achieve underground utopias.

Fragmented ownership, messy design

An important source of misalignment in the creation of underground paradigms originates from the fragmentation of authorities. With a few notable exceptions, underground mega-projects tend to be initiated by individual organizations - be they the energy grid company, the wastewater company, or governmental bodies for national infrastructures. As a consequence, multiple tunnels are bored into the depths of cities, each usually solving one single problem, disregarding potential benefits of a more comprehensive design.

A systemic approach to underground urbanism

We believe there is a significant gap between the enormous potential for designing visionary, future-proof utopias, on one side, and the institutional and methodological inadequacy of economic systems and governmental bodies in delivering such visionary paradigms, on the other. Capturing and planning for the long-term interests of multiple stakeholders can largely benefit from a holistic approach that goes beyond individual projects or networks.

An urgent, collective, multidimensional design of paradigms for the future of subsurface urbanism could include the following elements:

A broad, multi-stakeholder participation: This means involving a diverse range of actors, such as urban planners, architects, environmentalists, engineers, and civil servants, to ensure a holistic perspective that considers the various aspects of subsurface development.

A spirit of collective collaboration: Among the many stakeholders to be involved are the citizens, who must have a say in the discourse around urban subsurfaces, to balance the colonization process that replicates what happens above ground.

Enhanced collaboration across private and public: A sense of collective collaboration, fostering partnerships and cooperation among various stakeholders. Private sector entities bring innovation, investment, and technological expertise, while public entities contribute with regulatory frameworks, public infrastructure, and a commitment to community welfare.

Considering the impending challenges mentioned above, there is a need for urgent action, to design superior infrastructures and underground paradigms for the cities of the future. It is essential to unite all stakeholders under a shared vision, in order to acquire a deep understanding of the challenges to be addressed and the needs of users, and to design together visionary, long-term visions on the types of underground paradigms we desire. Central to this approach is the search for innovative, forward-looking solutions that are able to push the boundaries of conventional problem solving. This commitment to innovation is critical in developing sustainable and adaptive solutions that meet the needs of cities in the long-term.